Physicists like to think that all you have to do is say, these are the conditions, now what happens next? - Richard P. Feynman

The dominant “Newtonian” view or “classical science” is very linear. Every event is determined by initial conditions determinable with precision. A world in which chance plays no part. We have broken things into parts and fragments for so long and have believed that it is the best way to understand the world around us. We’ve done this for so long that we’ve become unable to visualize a different order that is there, moving as a whole.

The 18th century French mathematician, Pierre Simon de Laplace’s mission, was to know the world in a way so that every process and change that occurs, could be understood, predicted, and anticipated. Believing this was possible wasn’t necessarily a new development — people in science, philosophy, theology, and more have all tried to effectively forecast events based on past data.

However, we’ve never been able to accurately predict weather, wildlife populations, and the stock market perfectly. This total predictability and determinism didn’t exist due to the “chaotic” tendencies of these types of systems.

Chaos theory sought to challenge the prevalent view of how the world works (eg. a mechanistic view with simple, linear cause-effect relationships) and discovered new kinds of laws, associated with non-linear and complex dynamics. It focused on the strange phenomena of messiness, uncertainty, and disruption, that somehow results in self-organized order. And these laws of complexity hold universally, whatever the details: whether its the chemistry of neurons, aerodynamics in a wind tunnel, population growth, or the volatility of the financial markets.

Scale is also very important. Think about the universe all the way down to atoms. There is complexity, similarity, and beauty at every scale. Self-similarity is an old concept — popularized by fractals. At any scale, the part resembles the whole. Lungs, roots, snowflakes, rivers, electrical currents, coastlines, are all examples of self-similarity and fractals.

The most popular “example” of chaos theory is in the butterfly effect, defining the patterns of interaction and behaviour within particular trajectories or systems of change. It signifies a sensitive dependence on initial or starting conditions, emphasizing that even a microscopic fluctuation can send a complex, non-linear, chaotic system off in a new direction. In the case of the butterfly effect, a flutter of the wings of a butterfly, can cause a typhoon in a different location. As James Gleick says in Chaos, “Self-similarity is symmetry across scale. It implies recursion, pattern inside of pattern.”

Chaos is a condition through which order and disorder both flow simultaneously. Innovation rarely emerge from systems with high degrees of order and stability. Within chaos, the components of living systems self-organize and cause new conditions to emerge. When faced with turmoil and instability, parts of a system will network in new ways and undergo dramatic metamorphosis.

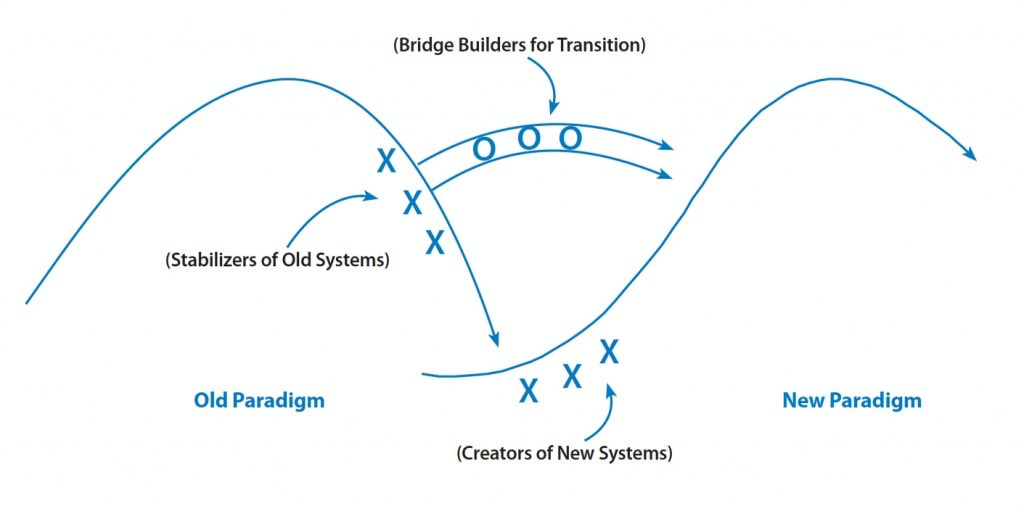

The Berkana Two-Loop Model is theory of change where, as one system peaks and begins to falter, alternatives start to arise in isolation. Slowly, the old collapses and the new arrises. The essential work within organizations and, in my opinion, innovation more globally, is to hospice the old, midwife the new, and build bridges between worldviews.

Path dependence depicts technologies as evolving through relatively long periods of stability and continuity, punctuated by relatively short bursts of fundamental, radical change. While sensitivity to initial conditions is generative of path dependence, like in any chaotic system, the possibility of path-breaking activity or sudden shifts is likely to occur because small variations can lead to major changes in a complex, dynamic system.

These principles of self-organization and emergence also apply to societies and economies. In the Bay Area, and now becoming more and more global due to remote work, scientists, academics, entrepreneurs, and investors all create strategic “alliances” between their companies and institutions to develop dramatic change.

However, on the other hand, equilibrium is death. If a company stays in one place or uses the same strategy for too long, their mechanisms for coping with change will erode. Change is inevitable. Blockbuster lost its competitive advantage in the 2000s when its stores dominated the market. Unwilling to deal with the turmoil that responding to the change would bring, the company leaders failed to adapt and stuck with its old strategies.

Operating within the fringes of chaotic systems and uncertainty, you have to find some semblance of a balance. You falter too much and you become unstable and die. You find too much stability and you stay stagnant and die. Uncertainty is good. Uncertainty is full of opportunity. It allows you to step back and see patterns and trends, assess the probability of certain outcomes and situations, evaluate risks and benefits of those situations, and capitalize on those opportunities in a systematic way. With too much uncertainty though, organizations and individuals get confused and die.

Andy Clark, in his book Surfing Uncertainty: Prediction, Action, and the Embodied Mind, argues that the mind is geared fundamentally towards prediction error minimization and uncertainty-reduction. Predictive Processing (PP), described by Clark is a paradigm in computational and cognitive neuroscience proposing that “perception involves the use of a unified body of acquired knowledge (a multi-level “generative model”) to predict the incoming sensory barrage”. Our predictive models in our head are what gives us the ability to conceive a coherent understanding of the world around us through the billions of raw data points it receives from our different senses.

Since birth, through our inherent curious nature, we start creating models that generate sense data. If a curious baby touches a candle and gets an ouchie, not much will happen — the baby might do it again. But what about after 2 or 3 times? What if that baby then touches the gas stove fire. Then the baby starts learning that maybe its the reddish-orange light that creates ouchie. And so on and so forth. Intelligence and knowledge is just meta-layers of previous experiences. We’re born to be curious, continuously learning and exploring — but not too curious because that’s also dangerous.

Jürgen Schmidhuber explains in his Formal Theory of Fun & Creativity that art, science, beauty, and even humour are byproducts of the desire to create/discover more data that is predictable but compressible in unknown ways. Something needs to be regular/symmetrical/predictable enough to be beautiful, but complex and unpredictable enough to draw and hold our attention.

As an example, “good” poetry and lyrics are a very satisfying mixture of predictability and unpredictability. With the basic alternate rhyme scheme (ABAB), the first and third lines rhyme at the end, whereas the second and fourth lines rhyme at the end. You begin to understand the pattern and structure, but you don’t know how exactly the writer will build it out completely. Same reason why the improv in jazz is so fascinating. Same reason why most people favour pop songs with VI IV V I chord progressions over Stravinsky. Too much irregularity with unfamiliar rhythm and tonality can lead to less of a subjective “reward”.

A typical hip hop song introduces the melody, a secondary melody, slowly adds in the hi hats, and then the rest of the drum pattern. It’s slowly feeding you information so that it’s not completely jarring as soon as the song comes on.

Whether its learning, art, beauty, science, or the cyclical nature of the economy and innovation, we appreciate a balance of both uncertainty and certainty. Of both balance and chaos. We appreciate things that are unique enough that it allows the “viewer” to discover something novel based on their prior experiences and knowledge, but less jarring than something completely foreign. We, as unfortunate as it may seem, appreciate incremental change, rather than moonshots.

All of this is pretty unfortunate to someone that believes we need more ambitious people and more daring ideas — more Elon Musk's and Vitalik Buterin’s and more SpaceX’s and Ethereums. However, I, as much as I also dislike incremental progress, believe that it’s essential for progress as a whole. Look at the three diagrams I just made:

How does society progress? As a whole? Individually as separate pieces where someone in one space is hoping the other pieces in another space align? Or within small niches of each of the larger categories?

I believe it progresses in each way simultaneously. There is a balance to everything. We need both the moonshots and the incremental progress. You can start a company but it’s just the wrong time for the market — the consumers aren’t ready for a change so drastic or the technology just isn’t developed as robust enough. In policy, a concept of the Overton window (aka the window of discourse) is used.

As I’m writing this article, Packy from Not Boring wrote a new article, The Laboratory for Complex Problems about Chaos and complex problems relating to the ebbs and flows of failure and success of crypto projects. Each NFT, DAO, DeFi project, are experiments run in bits to feed back into the world of Atoms.

I believe that, just how janitors and garbage cleaners provide an essential service to humanity, so does the random SaaS platform that saves freight companies 5 minutes per truck dispatch. It’s not earth shattering innovation but it progresses us ultimately in the right direction and is all needed for the greater whole. We need people working on the most ambitious of stuff just as much as we need people working on small projects that save us a couple of minutes a day.

Creativity and curiosity are the same aspects of the same principal within innovation — we’re all trying to make new and more data which is compressible in previously unknown ways. But in a way that it is not so novel that we’re completely dumbfounded when we encounter it.

To go back to the original title as to why innovation is slowing down, I’m honestly not too sure if it actually is. I didn’t do the research there. I’m personally conflicted whether we’re moving faster than ever or if we’re moving slower now with less ambition. 15 years ago we didn’t even have the iPhone. There’s so much information out there that it’s hard to consume and process it all in meaningful ways. Applied to innovation in the world, have we reached the point where we’re mostly bound to incremental progress? In the short fictional story Ars Longa, Vita Brevis, Scott Alexander talks about how, over time, more and more information is needed to consume to build on further developments and progress.

Overall, our Newtonian worldview has been disrupted over the last couple of decades. We found chaos, complexity, and self-organization within creativity and curiosity. From chaos theory, we learned that complex behaviour arises through the interactions of individual agents following simple rules. But chaos is fun.

By embracing the complexity of life and complex systems within, and through further opening yourself up to the nuances and subtleties of the human and world experience, we can get excited about the future of humanity. Despite the comfort in easy answers, things aren’t black and white. Chaos is fun. As Gleick says in Chaos, “chaos is a science of process rather than state, of becoming rather than being.”

Interesting Links:

Supposedly Microsoft Exchange formats date as YYMMDDHHMM and then stores that as a signed 32 bit int. 2201010001, the date for midnight January 1st, is larger than 2^31-1 so email servers crashed in a bunch of places.

Y2K22 bug stops Exchange mail delivery: Antimalware engine stumbles on 2022

Hi! 👋 I’m Razi Syed, currently focused on figuring out my place in the world. Thanks for reading my Newsletter! I’d love your feedback — feel free to tweet me @razisyed97.